Sentiment Analysis using word2vec

In this article I will describe what is the word2vec algorithm and how one can use it to implement a sentiment classification system. I will focus essentially on the Skip-Gram model. I won’t explain how to use advanced techniques such as negative sampling. Yet I implemented my sentiment analysis system using negative sampling. My code is available here and it corresponds to the first assignment of the CS224n class from Stanford University about Natural Language Processing with Deep Learning.

The idea behind Word2Vec

There are 2 main categories of Word2Vec methods:

- Continuous Bag of Words Model (or CBOW)

- Skip-Gram Model

While CBOW is a method that tries to “guess” the center word of a sentence knowing its surrounding words, Skip-Gram model tries to determine which words are the most likely to appear next to a center word. In a sense it can be said that these two methods are complementary. For the rest of the article, I will only focus on the Skip-Gram Model.

1. Skip-Gram Model: Intuition

1.1 Training task

Let’s say we want to train our model on one simple sentence like:

To do so we will iterate over our sentence and feed our model with a center word and its context words. See Figure 1.1 for a better understanding.

1.2 One-Hot representation

Well as we know, we cannot feed a Neural network with words as words have no meaning for a Neural Network (what is the meaning of adding 2 words for example?). We will then transform our words into numbers. One simple idea would be to assign 1 to the first word of our dictionnary, 2 to the next and so on. So for example, assuming we have 40 000 words in our dictionnary:

\[a \rightarrow 1 \\ aardvark \rightarrow 2 \\ \vdots \\ zebra \rightarrow 40000\]This is a bad idea. Indeed it projects our space of words (40 000 dimensions here) on a line (1 dimension) and loses a lot of information. To better understand why it is not a good idea, imagine dog is the 5641th word of my dictionnary and cat is the 4325th. If we substract cat from dog we have:

We can wonder why substracting cat from dog give us an abricot…

Hence, the naive simplest idea is to assign a vector to each word having a 1 in the position of the word in the vocabulary (dictionnary) and a 0 everywhere else. We call those vectors one-hot vectors.

\[a = \begin{bmatrix} 1\\ 0\\ \vdots\\ 0\\ \end{bmatrix} \ aardvark = \begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 1\\ \vdots\\ 0\\ \end{bmatrix} \ \ldots \ zebra = \begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ \vdots\\ 1\\ \end{bmatrix}\]To give you an intuition of why this representation is better, we can use the same example as before. Now, if I substract cat from dog I have a vector with 1 in the 5641th row, -1 in the 4325th row and 0 everywhere else. Therefore we see that this vector could have been obtain using only cat and dog words and not other words. The vector still have information about the word cat and the word dog. Of course this representation isn’t perfect either. These vectors are sparse and they don’t encode any semantic information. That is why we need to transform them into word vectors using a Neural Network.

1.3 Feeding the Neural Network

Now that we have a one-hot vector representing our input word, We will train a 1-hidden layer neural network using these input vectors. The hidden layer has no activation function and we will use a softmax classifier to return the normalized probability of a nearby word appearing next to the center word (input word). The architecture of this Neural network is represented in Figure 1.2:

Note: During the training task, the ouput vector will be one-hot vectors representing the nearby words. On the contray, when we evalute the model the ouput will be a probability distribution (a vector of length 40 000 and whose sum is 1 in our example).

1.4 The Hidden Layer

The idea is to represent a word using another representation then a one-hot vector as one-hot vector prevent us to capture relationship between words (synonyms, belonging, word to adjective,…). So we will represent a word with another vector. To do so we need to represent a word with n number of features (we usually choose n to be between 100 and 1000). The experiments show that 300 features is a good default choice. To have a 300 features word vector we will just need to have 300 neurons in the hidden layer. Hence our weight matrix has shape (300, 40000) and each column of our weight matrix represent a word using 300 features.

The idea is to train our model on the task describe in part 1.1. The Neural network will then update our weights and once the task is finished we will only be interested in the weight matrix as it represents each words with features that can capture relationship between words.

What is the effect of the hidden layer? As there is no activation function on the hidden layer when we feed a one-hot vector to the neural network we will multiply the weight matrix by the one hot vector. This will give us the word vector (with 300 features here) corresponding to the input word. See illustration in Figure 1.4 below.

1.5 The Ouput Layer

During the ouput layer we multiple a word vector of size (1,300) representing a word in our vocabulary (dictionnary) with the output matrix of size (300,40000). We will then have a (1,40000) ouput vector that we normalize using a softmax classifier to get a probability distribution. For example, with the word aardvark:

\[\text{input word (40000,1): } aardvark^{\intercal} = [0 \ 1 \ 0 \ \ldots \ 0] \\ \text{word vector (1,300): } aardvark = [1.2 \ -3.8 \ 0.17 \ \ldots \ 0.06] \\ \text{ouput vector (40000,1): } ouput^{\intercal}_{aardvark} = [0.001 \ 0 \ 0.00017 \ \ldots \ 0.00007]\]This process is also described in Figure 1.5 below:

1.6 Putting all together

To sum up we use one-hot vector to represent each word of our dictionnary (vocabulary), we then train a simple 1-hidden layer neural network using a center word and its context words. The neural network will update its weight using backpropagation and we will finally retrieve a 300 features vector for each word of our dictionnary. Those 300 features word will be able to encode semantic information.

Actually, if we are feeding two different words that should have a similar context (hot and warm for example), the probability distribution outputed by the neural network for those 2 different words should be quite similar. One way the neural network to ouput similar context predictions is if the word vectors are similar. Hence, if two different words have similar context they are more likely to have a similar word vector representation. This reasoning still apply for words that have similar context but that are not necessary synonyms. For example ski and snowboard should have similar context words and hence similar word vector representation.

2. Skip-Gram Model: Implementation

Now that we gain an intuition on how Skip-Gram model works we will dive into the real subject: How to implement a Word2Vec model (here Skip-Gram model)?

We saw in part 1 that, for our method to work we need to construct 2 matrices: The weight matrix and the ouput matrix that our neural network will update using backpropagation. As in any Neural Network we can initialize those matrices with small random number. The difficult part resides in finding a good objective function to minimize and compute the gradients to be able to backpropagate the error through the network.

2.1 Notation

We use mathematical notations to encode what we previously saw in part 1:

- Let $m$ be the window size (number of words to the left and to the right of center word)

- Let $n$ be the number of features we choose to encode the word vector ($n = 300$ in part 1)

- Let $v_i$ be the $i^{th}$ word from vocabulary $V$

- Let $|V|$ be the size of the vocabulary $V$ (in our examples from part 1, $|V| = 40000$)

- $W \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times |V|}$ is the input matrix or weight matrix

- $w_i: \ i^{th}$ column of $W$, the word vector representation of word $v_i$

- $U \in \mathbb{R}^{|V| \times n}$: Ouput word matrix

- $u_i: \ i^{th}$ row of $U$, the ouput vector representation of word $w_i$

2.2 Steps

We simply rewrite the steps that we saw in part 1 using mathematical notations:

- let $x \in \mathbb{R}^{|V|}$ be our one-hot input vector of the center word.

- we get the word vector representation: $w_c = Wx \in \mathbb{R}^n$ (Figure 1.4 from part 1)

- We generate a score vector $z=U w_c$ that we turn into a probability distribution using a softmax classifier: $\widehat{y} = softmax(z)$ (Figure 1.5 from part 1)

- We want our probability vector $\widehat{y}$ to match the true probability vector which is the sum of the one-hot representation of the context words that we average over the number of words in our vocabulary to get a probability vector.

2.3 Objective function

To be able to quantify the error between the probabilty vector generated and the true probabilities we need to generate an objective function. Here, we want to maximize the probability of seing the context words knowing the center word. Using math notations we want:

\[max \ J = P(v_{c-m},\ldots, v_{c-1}, v_{c+1},\ldots, v_{c+m} | v_c)\]Maximizing $J$ is the same as minimizing $-log(J)$ we can rewrite:

\[min \ J = -log[P(v_{c-m},\ldots, v_{c-1}, v_{c+1},\ldots, v_{c+m} | v_c)]\tag{2.1}\]We then use a Naive Bayes assumption. The Naive Bayes assumption states that given the center word, all context words are independents from each others. In practise this assumption is not true. For example if my center word is snow and my context words are ski and snowboard, it is natural to think that ski are not independant of snowboard given snow in the sense that if ski and snow appears in a text it is more likely that snow will appear than if John and snow appear in a text (John snow doesn’t snowboard…). In practise, using Bayes assumption still gives us good results. We can rewrite (2.1):

\[minimize [ -log \prod\limits_{j=0, j \neq m}^{2m} P(v_{c-m+j} | v_c) ] \\ = minimize [ -log \prod\limits_{j=0, j \neq m}^{2m} P(u_{c-m+j} | w_c) ] \\ = minimize [ -log \prod\limits_{j=0, j \neq m}^{2m} \frac{exp(u^{\intercal}_{c-m+j} w_c)}{\sum\limits_{k=1}^{\|V\|} exp(u^{\intercal}_k w_c)} ] \\ = minimize [ - \sum\limits_{j=0, j \neq m}^{2m} u^{\intercal}_{c-m+j} w_c + 2m.log \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\|V\|} exp(u^{\intercal}_k w_c)\tag{2.2}\]2.4 Implement the Skip-Gram model in Python

Assuming we have already implemented our neural network, we just need to compute the cost function and the gradients with respect to all the other word vectors. Finally we need to update the weights using Stochastic Gradient Descent.

Let:

- target be the index of the center word $v_o$. target (python) = o (in math)

- outputVector be the $U \in \mathbb{R}^{|V| \times n}$: Ouput word matrix

- predicted be $w_c$, the word vector representation of word $v_c$

We implement the cost function using the second to last relation from (2.2) and the previous notations:

\[probs = \frac{exp(u^{\intercal} w_c)}{\sum\limits_{k=1}^{\|V\|} exp(u^{\intercal}_k w_c)}\]and then we will retrieve the cost w.r.t to the target word with:

\[cost = -log(probs_{o})\]In python we can simply write:

probs = softmax( predicted.dot(outputVectors.T) )

cost = -np.log(probs[target])

This is almost what we want, except that, according to (2.2) we want to compute the cost for $o \in [c-m, c+m]$\{0}. We will do that later, it is quite straightforward. As $log(a \times b) = log(a) + log(b)$, we will only need to add up all the costs with $o$ varying betwen $c-m$ and $c+m$.

Now, let’s compute the gradient of $J$ (cost in python) with respect to $w_c$ (predicted in python). We use the chain rule:

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial w_c} = \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\|V\|} \frac{\partial J}{\partial f_k} \frac{\partial f_k}{\partial w_c} \\ \text{where $f_k = u^{\intercal}_k w_c$}\]We already know (see softmax article) that:

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial f_k} = \frac{\partial }{\partial f_k} \left( \frac{e^{f_o}}{\sum\limits_{j=1}^{\|V\|} e^{f_j}} \right) =\frac{e^{f_k}}{\sum\limits_{j=1}^{\|V\|} e^{f_j}} - \delta_{ko}\]Furthermore:

\[\frac{\partial f_k}{\partial w_c} = \frac{\partial u^{\intercal}_k w_c}{\partial w_c} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{d}{d w_{1c}}\left(\sum\limits_{i=1}^n u_{ki} w_{ic} \right)\\ \frac{d}{d w_{2c}}\left(\sum\limits_{i=1}^n u_{ki} w_{ic} \right)\\ \vdots \\ \frac{d}{d w_{nc}}\left(\sum\limits_{i=1}^n u_{ki} w_{ic} \right)\\ \end{bmatrix} = u_k\]Finally, using the third point from part 2.2 we can rewrite:

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial w_c} = \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\|V\|}\left[\frac{e^{f_k}}{\sum\limits_{j=1}^{\|V\|} e^{f_j}} - \delta_{ko}\right]u_k = \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\|V\|}(\widehat{y}_k - y_k)u_k = \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\|V\|}(\widehat{y} - y)_k \begin{bmatrix} u_{k1}\\ u_{k2}\\ \vdots \\ u_{kn}\\ \end{bmatrix} = (\widehat{y}-y)U\]To implement this in python, we can write:

# yhat - y

grad_pred = probs

grad_pred[target] -= 1

# dJ/dw_c

grad_pred.dot(outputVectors)

Using the chain rule we can also compute the gradient of $J$ w.r.t all the other word vectors $u$:

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial u_k} = w_c \left[\frac{e^{f_k}}{\sum\limits_{j=1}^{\|V\|} e^{f_j}} - \delta_{ko}\right] = w_c (\widehat{y}_k - \delta_{ko})\]and in python we can write:

grad = grad_pred[:, np.newaxis] * predicted[np.newaxis, :]

Finally, now that we can compute the cost and the gradients for one nearby word of our input word, we can compute the cost and the gradients for $2m-1$ nearby words of our input word, where $m$ is the size of the window simply by adding up all the costs and all the gradients. Indeed, according to the second to last relation from (2.2), we have:

\[log(\prod\limits_{k=0, k \neq m}^{2m} u_k) = \sum\limits_{k=0, k \neq m}^{2m} J_k \\ \text{where $J_k = log(u_k)$}\]As we already computed the gradient and the cost $J_k$ for one $k \in [0, 2m]$\{m} we can retrieve the “final” cost and the “final” gradient simply by adding up all the costs and gradients when $k$ varies between $0$ and $2m$.

In python, supposing we have already implemented a function that computes the cost for one nearby word, we can write something like:

for context_w in contextWords:

# index of target word

target = tokens[context_w]

cost_, gradPred_, gradOut_ = word2vecCostAndGradient(inputVectors[center_w], target, outputVectors, dataset)

cost += cost_

gradOut += gradOut_

gradIn[center_w] += gradPred_

return cost, gradIn, gradOut

3. Sentiment Analysis sytem

3.1 A simple model

A very simple idea to create a sentiment analysis system is to use the average of all the word vectors in a sentence as its features and then try to predict the sentiment level of the said sentence. Here we will use 5 classes to distinguish between very negative sentence (0) and very positive sentence (4).

So we will represent a sentence by taking the average of the vectors of the words in the sentence. In python we can simply write:

# indices of each word of the sentence (indices in [0, |V|])

listOfInd = [tokens[w] for w in sentence]

for i in listOfInd:

sentVector += wordVectors[i]

sentVector /= len(listOfInd)

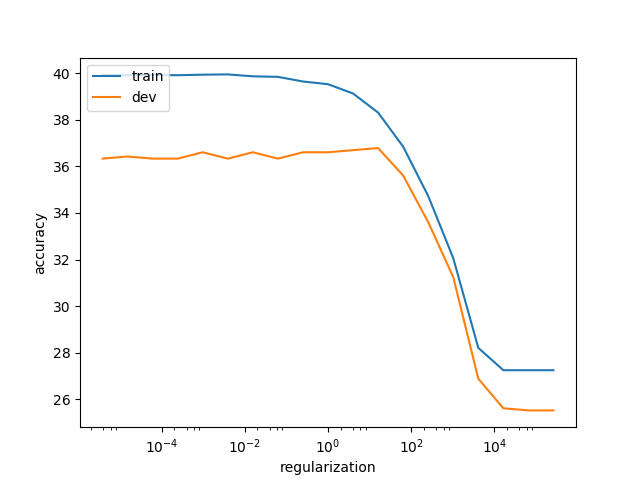

We will then just train our neural network using the vector of each sentence as inputs and the classes as desired outputs. Here we use regularization when computing the forward and backward pass to prevent overfitting (generalized poorly on unseen data). Using our system and pretained GloVe vectors we are able to reach 36% accuracy on the dev and test sets (With Word2Vec vectors we are able to reach only 30% accuracy). See Figure 3.1 below.

Our model clearly overfits when the regularization hyperparameter is less than 10 and we see that both the train and dev accuracies start to decrease when the regularization value is above 10. One good compromise is to choose a regularization parameter around 10 that ensures both a good accuracy and a good generalization on unseen examples.

3.2 Drawback of our model

One big problem of our model is that averaging word vectors to get a representations of our sentences destroys the word order. Hence I can have two sentences with the same words but having different classes (one positive the other negative) and our model will still classify both of them as being the same class. For example:

I don't like when you know something

Both sentences have the same words yet the first one seems to be positive while the second one seems to be negative. Our model cannot differentiate between these two sentences and will classify both of them either as being negative or positive. This is a huge drawback.

The fact that we destroy the word order by averaging the word vectors lead to the fact that we cannot recognize the sentiment of complex sentences. For example:

is clearly a negative review. Yet our model will detect the positive words best, hope, enjoy and will say this review is positive. In order to build a better model we will need to keep the order of the words by using a different neural network architecture such as a Recurrent Neural Network.

4. Conclusion

In this article we saw how to train a neural network to transform one-hot vectors into word vectors that have a semantic representation of the words. We also saw how to compute the gradient of the softmax classifier with respect to the word vectors. Finally we implemented a really simple model that can perfom sentiment analysis.

The attentive reader will have noticed that if we have 40,000 words in our vocabulary and if each word is represented by a vector of size 300 then we will need to update 12 million weights at each epoch during training time. It is obviously not what we want to do in practice. It exists other methods like the negative sampling technique or the hierarchical softmax method that allow to reduce the computational cost of training such neural network. Also one thing we need to keep in mind is that if we have 12 million weights to tune we need to have a large dataset of text to prevent overfitting.